Every journey conceals another journey within its lines: the path not taken and the forgotten angle. These are journeys I wish to record. Not the ones I made, but the ones I might have made, or perhaps did make in some other place or time. I could tell you the truth as you will find it in diaries and maps and log-books. I could faithfully describe all that I saw and heard and give you a travel book. You could follow it then, tracing those travels with your finger, putting red flags where I went.

Jeanette Winterson, Sexing the Cherry (1989)

I often find myself quoting Winterson in relation to my background research, and will again later. This passage appealed because it adds shade to what follows. It speaks of walking in terms of myth, alternative dimensions, and lines! As my project moves into another phase, to recap the story so far…

During my doctoral research I developed a precarious interest in the notion of ‘earth energies’ as a way of conceptualising and mapping landscapes, especially ones that are treated as ‘sacred’ and attract ritual and/or artistic behaviour. Thankfully, I avoided that immediate abyss, but Public Archaeology 2015 has provided me with the impetus to develop this idea through art practice. So my project is the archaeology of an idea, where I look closer at one element of a continuous ‘deep map’, if you will, of Avebury’s ritual landscape. After a hesitant gestation during the first half of the 20th century, the myth of English earth energies (subsumed into the myth of ‘ley’ lines, as prehistoric pathways) gained traction during the mid-to-late 1960s and the countercultural beginnings of the New Age movement. I don’t subscribe to the view of some academics that this antistructural ideology sits in opposition to “the mainstream”, because New Age ideas have by now atomised to the extent that many are integrated into wider society. One of these is that of the St. Michael ‘ley’ line, which stretches some 350 miles from Carn Lês Boel in Cornwall, through Glastonbury, Avebury, Bury St Edmunds and other holy sites, to Hopton-on-Sea on the East Anglian coast, in alignment with the path of the Beltane sunrise. As a postmodern movement, the New Age is distinctly pre-modern in its leanings. Its fascination with cultural archaeology via the performance of ritual practice is first and foremost an nostalgic escape from modernity to a time conceived of as a prehistoric (i.e., mysterious) past, a tabula rasa on which to inscribe new histories. Winterson again: “The past is another country, but one that we can visit, and once there we can bring back the things we need”.

The Michael line is a quasi-object that acts as a way of reclaiming that past and making it real. As such, it shows the importance of place in these mythospiritual negotiations. Yet, in drawing attention to the imaginary nature of the Michael line, it would be unfair to describe it as non-physical and to allow it on that basis to be thought of as non-existent, because it does have a material, visible dimension. Memories, even false ones, are [observed Edward Casey in Remembering: A Phenomenological Study (1987)] ineluctably place-bound. Just as archaeology is a useful method of ‘re-membering’ something we have not lived as direct experience, ritual processes of remembering are a way of articulating our relationship with the people who lived the past, a kind of ad hoc living archaeology but performed, in the present, as futurological wish-fulfillment. The task of place is to congeal this poetic imaginary into a provisional reality. Casey advises that rather than thinking of memory as a form of re-experiencing the past, it can be conceived of as a kind of re-placement activity, where we re-experience past places.

And so it was that John Michell conceived of the St. Michael line as he stood on top of Glastonbury Tor, a terraced, natural prominence in the Somerset levels that stands as an icon of the local mythos. At its summit is a ruined tower. Visible some 11 miles to the southwest is a solitary hill, or mump, similarly adorned with a ruined church dedicated to St Michael. Michell noticed that:

The Tor and the Mump have another feature in common, their orientation. The axis of the Mump is directed towards the Tor, where the line is continued by the old pilgrim’s path along the ridge of the Tor to St Michael’s tower. This line drew attention to itself and demanded investigation, so I extended it further east, and the result confirmed its significance. The line went straight to the great stones at the entrance to the megalithic temple at Avebury.

John Michell, review of Broadhurst & Hamish Miller’s The Sun and the Serpent (1989)

In Michell’s hands, the line and an ancient track called the Icknield Way were one and the same. This is a typical ‘New Age counterfactual’ which makes sense only in its own legend context, but gives validity to the myth. Michell was unconcerned with being proved wrong by mainstream historians, only, in line with his antistructural aims, in persuading his readers that conventional history is wrong. He identified the ‘ley’ as a fragment of lost knowledge of a bygone Golden Age, consistent with Newton’s and Stukeley’s, and subsequently Blake’s vision of a British Eden: Old Albion.

Jerusalem the Emanation of the Giant Albion! Can it be? Is it a Truth that the Learned have explored? Was Britain the Primitive Seat of the Patriarchal Religion? If it is true: [it] is also True that Jerusalem was & is the Emanation of the Giant Albion. It is True, and cannot be controverted. Ye are united O ye Inhabitants of Earth in One Religion. The Religion of Jesus: the most Ancient, the Eternal: & the Everlasting Gospel – The Wicked will turn it to Wickedness, the Righteous to Righteousness. Amen! Huzza! Selah! ” All things Begin & End in Albion’s Ancient Druid Rocky Shore.”

William Blake, Jerusalem (1804)

Inspired by this revelation, in 1988, at around the time Jeanette Winterson was writing the epigraph above, Michell’s friend Paul Broadhurst and a dowser, Hamish Miller, set off on an expedition to map the Michael line. The resulting book, The Sun and the Serpent became an instant cult classic, a sacred text which galvanized this assemblage of quasi-religious ideas under the aegis of Earth Mysteries, a ‘scientific’ tributary of New Age thought. Michell, of course, wrote the Introduction, where careful reading reveals a clever method of circular referencing: Broadhurst & Miller’s expedition and findings are used to validate an idea of which Michell himself was the source. This process of accretion is how myths are made, and survive. It’s also worth noting that Michell came up with the idea on Glastonbury Tor, and that the direction of the line was determined by its geography, and because of that it happened to end up in the places it did. Somehow, by starting at one end, it seems more significant (there’s no such thing as coincidence in New Age thinking) that the Tor is situated upon it. (I was surprised too, until I thought about it.) That is not to diminish its coincidences, however.

Today’s conception of ‘ley’ lines as electromagnetic currents maintains a geographical bearing in terms of Watkins’ ‘old straight track’ as together they make a spiritual map of the land, binding a demesne of the mind in which ‘lost’ ancient wisdom is preserved in code within the landscape. Crucially, it draws attention to the Avebury complex, which to Michell was a major place of convergence of ancient tracks and energy lines. Accordingly, as Delphi was to the Greeks, so was Avebury to the ancient tribes. As Broadhurst writes elsewhere, “it is almost as if [this code] was intended to reappear to us at a time when most needed, to remind us of the higher principles that guided our ancestors.” This premise carries the inference that these lines and currents formed networks and nodes, which dictated where the ancients had located their monuments, or added to existing topographical features (such as Glastonbury Tor) and this is the path the myth of ley lines has followed over the last thirty years or so. But it was more than inference: “We can only conclude that these sites were discovered using some form of divination”, wrote Michell in an article for International Times in 1968. Miller, as an expert dowser, provided a tangible link to Britain’s prehistoric past that is perceptible by the senses, especially the sense of touch, and capable therefore of being treated as fact. However, in this era of thingness I would argue that these vestigial man-made remains, themselves cultural, semiotic objects, are performative in that they influenced Miller to perform, leading Broadhurst and him, and their readers, to imagine flowing currents undulating like rivers between sites that not only mark but also effect their course. Again, a circularity of logic that excludes the possibility that dowsing might be at once both the technology and the product of enchantment. (Let’s be mindful here that herms are boundary markers that show where the mythical Trickster figure Hermes has trodden.)

Psychologists who study this topic (notably Prof. Christopher French at Goldsmiths College) have identified this circularity as the ideomotor effect, subtle non-conscious movement of the human body caused by dual senses of expectancy and receptivity, which combine to influence and even drive this process through reciprocity. In his poem Description Without Place (1945), Wallace Stevens defined this kind of creative response as “an expectation, a desire … a little different from reality, the difference that we make in what we see.” Obviously, this contradicts the dowser’s own belief that the rods move independently of human influence; accordingly, these sensitives merely channel the flow of energy to the rods. This may be exacerbated by the popular notion that, in the right hands, measuring instruments are assumed to confer non-interventionist objectivity over human fallibility. But, as extensions and enhancements of the body they can also magnify subjectivity. The camera and dowsing rods are both examples of tools that are thought not to lie but are utilized to that end when regression to less perceptive reasoning is required to interpret occult phenomena. (As Pennick & Devereux observed in 1989, “dowsing rods have become the implement to authorize the acceptance of subjective ideas as factual statements.”)

Or is it more perceptive? This is where Winterson’s journeys concealing other journeys is so relevant, and to the wyrd turn that I can sense my contribution to PA2015 is about to take. Let’s consider Phil Smith’s model of mythogeography in this context, where we, as counter-tourists, and occasionally zombies, subject the sites we visit to our own unique associations, stories and reconstructions – rather than passively consuming official information, we become the agents of our own interpretations. The Situationists defined psychogeography as ‘the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment on the emotions and behaviour of individuals.’ Mythogeography opens this up to include the effect of myth and legend on the way we perceive certain environments and how this affects emotions and behaviour. On the strength of this, I would regard Miller as a proto-mythogeographer. Mythogeography is indigenous to the countercultural realm of the wyrd that Michell, Broadhurst and Miller inhabited. As do I, hence my decantation: Mythoarchaeology – likewise, mythoarchaeology deploys ways and means to change or heighten existing perceptions of place, utilizing the myth of archaeology as a science through the use of material evidence, instrumentation and data. In parodying science it actuates performativity and subverts orthodox knowledge. This kind of exploration embraces Glyn Daniels’ refreshing disrespect for the servitude to received wisdom implied in his remark that “the problem in archaeology is when to stop laughing.” [(1961) Editorial, Antiquity 36: 63-4].

The Site

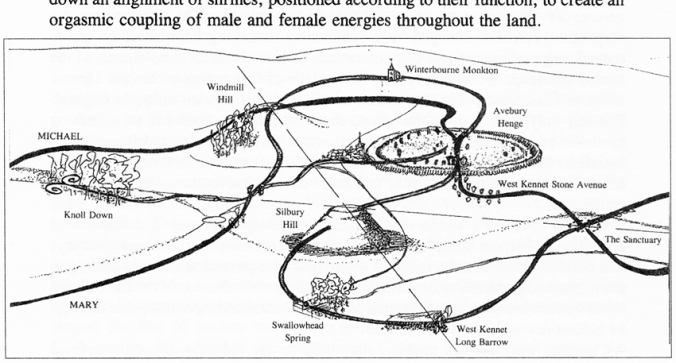

My choice of site is in the area where Broadhurst & Miller discovered the ‘feminine’ Mary line as it deviates from the route of the Michael line along the avenue of standing stones that links the Avebury henge to the Sanctuary (see photo above), and snakes (sashays?) through Silbury Hill, Swallowhead spring and West Kennet long barrow before rejoining her consort at the Sanctuary. Here’s how Broadhurst describes their immanent, animistic, zoomorphic vision:

From Broadhurst & Miller’s The Sun and the Serpent, showing where the Michael and Mary lines’ converge at Avebury. It was here, on our first day, where Inesa reported feeling an energy hotspot.

We had followed this serpentine energy for 150 miles. It had performed many strange contortions on its route across country. Here, for the first time, marked out by rows of standing stones, was a graphic display of how the energy actually operated. It was organic; it flowed without regard for human perceptions of symmetry and order. One minute it could be wide and gentle, the next narrow and sinuous. Like a river, it formed curves and eddies, all of which were accurately laid out in stone. […] The serpent ran right though the circles. There was some confusion. Another current joined it, crossing at the centre. The reactions were checked. There was no doubt. There was another serpent. One that appeared to be a different frequency but just as powerful. It entered through a group of prominent tumuli over the road, ran through the gate and the only remaining original stone, and […] head[ed] off to the south-west. The St Michael serpent entered at the neck of the stone avenue and ran towards the south-east.

Broadhurst & Miller, The Sun and the Serpent (1989)

Miller’s diagram of the intertwining serpentine movement of the Michael and Mary lines at Avebury. The site of our geophysical survey sits between Swallowhead Spring and West Kennet long barrow.

The Catholic Encyclopedia of 1912 pithily observed that once numinous experiences are localised, pilgrimages necessarily follow. This may be doubly true, I suppose, when the place itself is imbued with creaturely life. Today, Avebury’s ritual landscape area is as popular a place of spiritual refuge and enquiry as any other holy site, and the annual arrival of hundreds of thousands of mystical tourists suggests that the place, as setting, represents an interface where human conceptions of occult otherness exist to be revealed. Michell, Miller and crop circle-makers have all played a part in this transformation. As an artist, I don’t see my role as debunker; quite the opposite, I would aim to subvert the kind of order-directed explanationism that modern society tends to manufacture, in favour of a healthy plurality of ideas. Isn’t that what artists are for?

From here until my walk, as images become available in the next few days I’ll let them do my talking. My hope is that in one way or another they contribute to the ontological and epistemological tensions I’ve described above by encouraging public engagement. Hopefully laced with dispute, because dispute lies at heart of my subject matter. Folklorist Linda Dégh observed that this is more than a feature of legend: “it is its very essence, its raison d’être, its goal, for legend demands answers, but not necessarily resolutions.”

I’m walking and talking this landscape on 1 Feb, a Sunday. Anyone is welcome to join me – please see A Geophysical Study of ‘Earth Energies’ in Avebury’s Ritual Landscape using a Magnetic Susceptibility Field Coil or Mythoarchaeology on Facebook for details.

Fascinating Rob, I’m following this with real interest. My thoughts are still forming, but I think including myth and legend into the ‘deep map’ (for want of a better term) is such a productive avenue. There’s so much here, and it’s such a rich project. I’m gutted I can’t make it up for the walk, but I hope you get a good crowd. The literary quotes made me wonder if you’ve read the Bold As Love series by Gwyneth Jones, well worth it if you haven’t, and I think there might be some interesting chimes there. E.B

Thanks Elizabeth, and apologies for not replying sooner. Alternatively, an ‘oblique map’, though I think ‘deep map’ is better. I agree about the productivity of not dismissing 80% of hearsay as superfluous – instead, listening to it and even acting on it too. An example of this emerged from meeting Brian Edwards on the morning of our walk, and his suggestion that I should read the Drax letters (concerning the earliest excavations on Silbury Hill) very carefully. It added new layers, most probably of the mythical sort, to the map, but also interesting fact that I wasn’t aware of. The fact that this approach and its realisation one way or another affects our perceptions of place is enough to get me interested.

Thanks for the Gwyneth Jones reference. I didn’t know about it and I’ve looked it up – a good start. And I’m really looking forward to reading / hearing about your own journeys on the Downs.

Pingback: Geophysical Study of ‘Earth Energies’ in Avebury’s Ritual Landscape using a Magnetic Susceptibility Field Coil | Public Archaeology 2015

Hi Rob,

Really interesting to read this. I’ve always been fascinated by Avebury, not for its ‘true’ past, but more for the odd way in which every time I have visited has been at a completely different point in my life and I view the place in a lot of different ways simultaneously. So, I’ve done the fieldtrip where we worked out smugly that it was built in the 1930s, but I’ve also been there in the snow a couple of days before Christmas talking to druids in the Red Lion (pre-conversion!), and driven there with colleagues after a day excavating a Romano-British cemetery nearby. I could talk a lot about Avebury, but I know very little about its ‘official’ story.

You might be interested in my last visit in 2008. I walked to Avebury from Glastonbury with a group of walkers on a walk called Awakening Albion. There was a core group of nine who left Carn Les Boel in Cornwall at Beltane sunrise and arrived at Hopton in Norfolk for sunrise on the summer solstice. You’ll have noticed that the straight line between them is an approximation of the Michael and Mary lines, and that provided the route for the walk. I joined them for a few days at the end of May/early June. I’ll tell you about it properly sometime, but for now you may be interested in some photos from the walk. They’re on Facebook, and I think I’ve set them to public properly, let me know if not. Oh, and there’s a book, link at the bottom!

Day 1: Glastonbury: https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.18805727540.37789.638437540&type=1&l=8326ab21e7

Day 2: Glastonbury to Cranmore Tower: https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.18806632540.37790.638437540&type=1&l=4a1ae663c2

Day 3: Cranmore Tower to Hooper’s Pool: https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.18807467540.37791.638437540&type=1&l=ca5c0afe28

Day 4: Hooper’s Pool to Sells Green: https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.18808012540.37793.638437540&type=1&l=eed0a342fc

Day 5: Sells Green to Avebury: https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.18809402540.37795.638437540&type=1&l=0df6363e6f

Day 6: Avebury: https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.18810592540.37797.638437540&type=1&l=b3232be76b

And the book: http://www.amazon.co.uk/Awakening-Albion-Cornwall-Together-Community/dp/0952439689